Above: "The Pied Piper," a lithograph on ivory wove paper, by Albert James Webb (1891-1958), created while he was in the WPA's art program, ca. 1935-1942. There is very little information on the Internet or in newspaper archives about Webb; but according to the website Art of the Print, he was a "talented New York City painter, etcher and lithographic artist" and "studied at the Art Students League." Also, Find a Grave shows that he was a private in the U.S. Army. Perhaps he served during World War I, and perhaps his memories of the war motivated his Grim Reaper-style Pied Piper. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, used here for educational and non-commercial purposes.

Periodic posts about the most interesting time in American history: The New Deal!

Monday, June 26, 2017

Sunday, June 25, 2017

Kansas City Colossus, courtesy of the Public Works Administration

Above: A PWA-constructed auditorium in Kansas City, Missouri, ca. 1936. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: The PWA-constructed auditorium in 2008. Photo courtesy of "Charvex" and Wikipedia.

Saturday, June 24, 2017

New Deal Grandeur in Indiana

From an era of proud American infrastructure and a government for the people, both so completely absent today, here's a little New Deal grandeur in Indiana. (Unless otherwise noted, photos courtesy of the National Archives.)

Above: A New Deal field house at Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal war memorial in Indianapolis, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal dorm for women at Purdue University, in Lafayette, Indiana, for the people.

Above: Another New Deal dorm for women, this one at the University of Indiana in Bloomington, for the people.

Above: A New Deal school for African Americans in Indianapolis, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal firehouse in Avilla, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal courthouse in Shelbyville, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal disposal plant in Gary, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal training building for teachers, at the University of Indiana in Bloomington, for the people.

Above: A New Deal naval armory in Indianapolis, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal power plant in Columbia City, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal medical building at the University of Indiana in Bloomington, for the people.

Above: A New Deal civic center in Hammond, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal administration building at Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana, for the people.

Above: A New Deal art building at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, for the people.

Above: The New Deal art building today, still serving the people as an art museum. Photo courtesy of Ball State University, used here for educational and non-commercial purposes.

Thursday, June 22, 2017

New Deal Magnificence in Nebraska

In this dark age of bland architecture, infrastructure neglect, and Republican tax cuts for the nation's super-wealthy money-hoarders, it's nice to look back at a time when policymakers actually cared about the country as a whole. Look at some of these splendid buildings & structures in Nebraska, built by the New Deal between 1933 and 1943, for the people. You're highly unlikely to see anything like these built today, as the modern emphasis is on cheap and boring (if anything at all) - I mean, let's face it, our rich CEOs & celebrities MUST have their private compounds, private islands, and private jets, and we MUST plutocratize nations around the world with our endless & highly expensive military adventures. And so, after all that, there just isn't much left for the common good. (All photos courtesy of the National Archives.)

Above: A New Deal bandstand in Kearney, Nebraska, for the people.

Above: A New Deal auditorium in Freemont, Nebraska, for the people.

Above: A New Deal swimming pool facility in Kearney, Nebraska, for the people.

Above: A New Deal building for the University of Nebraska, in Omaha, for the people.

Above: A New Deal powerhouse and surge tank in North Platte, Nebraska, for the people.

Above: A New Deal airport hangar in Grand Island, Nebraska, for the people.

Above: A New Deal bandstand in Stanton, Nebraska, for the people.

Above: A New Deal war memorial at Antelope Park, in Lincoln, Nebraska, for the people.

Saturday, June 17, 2017

New Deal Fairy Tale, Nursery Rhyme, and Story Art (10/10): "Goldilocks and the Three Bears"

Above: "Goldilocks," a ceramic sculpture by Emilie Scrivens, created while she was in the WPA's Federal Art Project, ca. 1935-1938. Image courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library.

Above: "Three Bears," another ceramic sculpture by WPA artist Emilie Scrivens. There is hardly any information about Scrivens on the Internet, or in newspaper archives, but according to one art vendor, Scrivens "began an intensive study of pottery, sculpture, and mold-making as a WPA artist in the Federal Art Project of Cleveland, under Edris Eckhardt [see my blog post here]. Over time, her skills improved sufficiently that she won awards from the annual May Show of the Cleveland Museum of Art." Image courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library.

Above: A National Youth Administration (NYA) worker reads a story to nursery school kids in Los Angeles, 1941. During the New Deal, the NYA hired millions of teens and young adults to do useful public work. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A National Youth Administration (NYA) worker reads a story to nursery school kids in Los Angeles, 1941. During the New Deal, the NYA hired millions of teens and young adults to do useful public work. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Friday, June 16, 2017

New Deal Fairy Tale, Nursery Rhyme, and Story Art (9/10): WPA posters, WPA theatre

Unless otherwise noted, the images below are from the George Mason University Library, used here for educational, non-commercial purposes. The production information comes from the 1940 book Arena, by WPA Theatre Director Hallie Flanagan.

Above: A WPA poster for Treasure Island. The WPA performed Treasure Island in New Jersey from November 11 through December 30, 1937; put on a puppet show in Miami on March 10, 1939; and another puppet show in New York City from July 12, 1935 through March 26, 1936.

Above: A WPA poster for Jack and the Beanstalk. This WPA performance ran from August 17, 1937 through March 10, 1938.

Above: A costume design for the WPA production of Aladdin. The WPA performed Aladdin in Los Angeles, from March 11 through July 22, 1938.

Above: A WPA poster for Robin Hood. This WPA musical played at the Emery Theatre in Cincinnati from December 27, 1937 through January 8, 1938.

Above: A WPA poster for Pinocchio. In addition to this production in Boston, the WPA performed Pinocchio in Los Angeles from June 3, 1937 through December 3, 1938.

Above: A set design for the WPA production of Robinson Crusoe. The WPA performed Robinson Crusoe in Gary, Indiana, from May 22 through August 18, 1937.

Above: A WPA poster for Alice in Wonderland. The WPA performed this puppet show from April 9 through April 20, 1938. Also, WPA actors performed Alice in Wonderland in Portland, Oregon, from December 26, 1938 through January 14, 1939, and in New Haven, Connecticut from March 16 through April 28, 1936.

Above: A WPA poster for Revolt of the Beavers. The WPA performed Revolt of the Beavers in New York City from May 20 through June 17, 1937. Revolt of the Beavers was written in 1936 by Oscar Saul and Louis Lantz and caused a controversy when it was performed by the WPA in 1937 (see next caption).

Above: A scene from the WPA production Revolt of the Beavers. In her 2008 book, Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art Out of Desperate Times, writer Susan Quinn explained how the play created a brouhaha: "Revolt was a fairy tale with a message: It told the story of a cruel beaver chief who keeps the underling beavers busy turning bark into products but shares none of the proceeds from their labor. A hero beaver named Oakleaf organizes the beavers and leads them in a revolt. They shoot down the company's police, using revolvers and machine guns concealed in their lunch boxes, then gleefully send their oppressors into exile" (p. 160). Children loved the play, especially the parts where the actors moved around on roller skates. However, political conservatives were less-than-happy. Revolt of the Beavers added to their suspicion that the WPA Theatre was spreading subversive communist thought, and was a dangerous challenge to plutocracy, economic hoarding, and institutionalized oppression. (Also see, Brooks Atkinson, "'The Revolt of the Beavers,' or Mother Goose Marx, Under WPA Auspices," New York Times, May 21, 1937). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

*****

In addition to the stories above, the WPA Theatre also performed drama or puppet shows of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, Tom Sawyer, Beauty and the Beast, Cricket on the Hearth, The Emperor's New Clothes, Rip Van Winkle, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and more.

Thursday, June 15, 2017

New Deal Fairy Tale, Nursery Rhyme, and Story Art (8/10): The Mother Goose mural that children saved, but cultural apathy lost

Above: This grainy black & white photo of Bernice Cross's color WPA mural (see discussion below) is from the December 2nd, 1937 edition of the McComb Enterprise-Journal newspaper (Mississippi). It may be the only photo of Cross's mural, and was featured in many newspapers across the country, after a government official insulted it in 1937. (The photo is used here for educational and non-commercial purposes.)

The WPA mural that was called grotesque, saved by children, and then lost by cultural apathy

The WPA mural that was called grotesque, saved by children, and then lost by cultural apathy

WPA artist Bernice Cross (1912-1996) painted the above Mother Goose mural--featuring Old King Cole, Humpty Dumpty, and other nursery rhyme characters--for the children's ward at the Glenn Dale Hospital (Prince George's County, Maryland), ca. 1935-1937. The mural caused a national sensation in 1937 when a Washington, D.C. health official called it "grotesque" and ordered its destruction. However, in response to the condemnation, a jury of six children was formed to judge the mural and determine its fate.

The first child-juror brought in to judge the mural was asked, "Are you interested in this?" to which she replied, "Yes, it's very pretty." An African American child, whose eyes were transfixed on "the king about to eat a blackbird pie" said, "I think it is very nice." The other children agreed and the mural was saved (see, e.g., "Jury Of Children Saves Mural On Mother Goose," The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), November 25, 1937).

Unfortunately, Cross's mural was later lost, as explained in a Maryland Historical Trust form: "The mural was described as being located on the left side of the lobby as one entered the children's hospital building, covering the whole wall above the wainscoting. It is no longer there and it is not known if it was painted over or removed" ("Glenn Dale Hospital," Individual Property/District, Maryland Historical Trust Internal NR-Eligibility Review Form, 1997, section 8, p. 7).

Cross's Mother Goose mural is not the only New Deal artwork to be lost or forgotten. Many thousands are unaccounted for, and many others are not on display. However, there are quite a few organizations, e.g., the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Living New Deal, and the federal government's General Services Administration, that are trying to find, inventory, display, or preserve these national treasures. Hopefully, a large New Deal Museum will one day house and display New Deal paintings, sculptures, wood carvings, lithographs, and more.

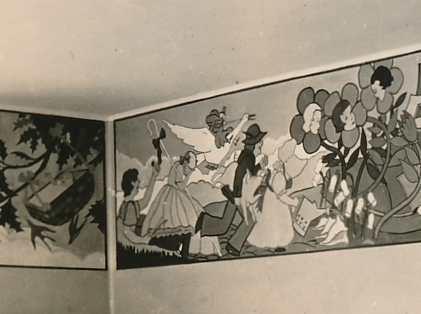

Above: The Mother Goose mural in this WPA photograph (taken at a children's hospital in Portland, Maine, ca. 1935-1939) was most likely painted by a WPA artist (see, e.g., "Children's Hospital Mural - Portland ME," Living New Deal, accessed June 15, 2017). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A closer look at the mural, showing Mother Goose, Little Bo Peep, and others. The idea behind these murals was to provide a more cheerful atmosphere for convalescing children. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: "Little Jack Horner," a ceramic sculpture by Edris Eckhardt (1905-1988), created while she was in the New Deal's Public Works of Art Project, ca. 1933-1934. Little Jack Horner is a famous Mother Goose nursery rhyme (however, the fictitious boy apparently dates back to the 1700s). The rhyme goes like this: "Little Jack Horner sat in the corner, eating a Christmas pie; He put in his thumb and pulled out a plumb, and said "What a good boy am I!." Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library.

Wednesday, June 14, 2017

New Deal Fairy Tale, Nursery Rhyme, and Story Art (7/10): Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox

Above: "Clearing Tacoma Flats," a linocut by Richard V. Correll (1904-1990), created while he was in the WPA's Federal Art Project, 1940. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Sheldon Museum of Art.

Above: "Making San Juan Island," another WPA linocut by Richard V. Correll, 1940. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Sheldon Museum of Art.

Above: "Paul Bunyan Sleeping," another WPA linocut by Richard V. Correll, 1940. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Sheldon Museum of Art.

Above: A mural at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, showing Paul Bunyan, Babe the Blue Ox, and two workers. This mural, part of a larger set, was created by James Watrous (1908-1999), while he was in the New Deal's Public Works of Art Project, ca. 1933-1934. Image courtesy of the University of Wisconsin.

Above: A stained glass mural of Paul Bunyan and Babe, at the Timberline Lodge in Oregon, created in 1938 by WPA artist Virginia Darce. The mural was restored in 2011, after suffering water damage ("Hillsboro mural artist assists with historic Timberline project," The Oregonian, January 4, 2011). Photo courtesy of Carol M. Highsmith and the Library of Congress.

Above: A statue of Paul Bunyan and Babe - see information below. Image courtesy of the University of Oregon Libraries, used here for educational and non-commercial purposes.

Above: A statue of Paul Bunyan and Babe - see information below. Image courtesy of the University of Oregon Libraries, used here for educational and non-commercial purposes.

A Mysterious Paul Bunyan and Babe Statue

The Paul Bunyan and Babe statue you see above is a bit of a mystery, but it might very well be a New Deal art project. It was sculpted by Oilver L. Barrett (1892-1943), a professor at the University of Oregon, ca. 1935. Piecing together various sources of information, it appears this sculpture may have been part a years-long ambition of Barrett's to create a larger version, and have it placed at a public venue.

Barrett is listed on the Wikipedia page "List of Federal Art Project artists." He also participated in the New Deal's Public Works of Art Project (see, Public Works of Art Project, Report of the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury to Federal Emergency Relief Administrator, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934, p. 85). Additionally, on February 19, 1937, The Eugene Guard newspaper reported that a Federal Art Project official visited the University of Oregon and, among other things, praised Barrett's statue "Paul Bunyan and the Blue Ox," and recommended it be placed somewhere in the Pacific Northwest, to attract worldwide visitors. Does this mean that, by 1937, a full-scale version of the statue had been completed? It's unclear, but on March 1, 1945, in an article about an exhibition of Barrett's work, a journalist for The Eugene Guard wrote: "Although Barrett's sudden death prevented his realizing his greatest ambition--to depict the figure of Paul Bunyan, hero of the logging industry--his work, nevertheless, was shown in an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City before his death" ("Barrett Sculpture Exhibited"). Presumably, the journalist meant: "to depict the figure of Paul Bunyan" in a prominent public place.

Professor Barrett died a sudden death in 1943, at the age of 50. In a tribute to his life, it was noted that he was an animal lover, and his art studio was always filled with homeless cats and dogs ("Oliver Laurence Barrett," The Eugene Guard, August 9, 1943, p. 3).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)