Above: "Champion Defeat," a watercolor painting by George Schreiber (1904-1977), created while he was in the New Deal's Public Works of Art Project, 1934. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Museum of the City of New York.

Above: A close-up of the unruly crowd in Schreiber's "Champion's Defeat."

Above: "Right Hook," an artwork by Dayton Brandfield (1911-1993), created while he was in the WPA's Federal Art Project, ca. 1935-1939. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Ackland Art Museum.

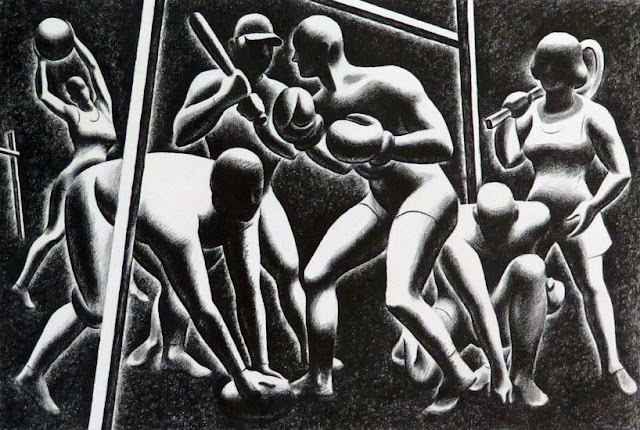

Above: "The Set Up," a lithograph by John W. Beauchamp (1906-1957), created while he was in the WPA, ca. 1935-1943. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Gibbes Museum of Art.

Above: "Down and Out," a painting by Barnett Braverman (1888-?), while he was in the WPA's Federal Art Project, 1937. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Genessee Valley Council on the Arts.

Above: A WPA poster, advertising an event for the New Deal's National Youth Administration (NYA). Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

WPA Boxing

Boxing was very popular during the 1930s, and the WPA catered to this interest by offering boxing lessons and boxing tournaments. For example, in the November 7th, 1940 edition of

The News newspaper (Paterson, New Jersey), the following was advertised: "In conjunction with the county WPA Recreation program, boxing lessons are given each Tuesday at the Pompton Lakes High School by Paul Cavalier, former heavyweight" (for boxing fans, see Paul Cavalier's biography on the

website of the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame).

In the January 5th, 1937 edition of the Daily Clintonian (Clinton, Indiana), we read: "Clinton's WPA amateur boxing team is scheduled for another match Friday, January 15, recreation officials announced today. The Washington Panthers will appear here at the Coliseum for a seven-bout evening of pugilistic entertainment" ("WPA Boxers to Meet Panthers").

These types of stories are all throughout newspaper archives, and speak to the popularity of boxing at the time, as well as the prevalence of WPA recreation activities related to the sport.

Boxing can be brutal; however, when taught in conjunction with good sportsmanship (which seems to be lacking in many fighting sports today), and when appropriate head gear is used (as we see in Golden Gloves and Olympic boxing), and with limited rounds (3-5?), perhaps there is something to be said for its physical fitness qualities and its cathartic release of aggression.

Above: A group of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) boxers in California, 1933. When not performing their forestry work, CCC enrollees could participate in a variety of recreation programs. Interestingly, WPA boxers sometimes fought CCC boxers (see, for example, "WPA Boxers Top CCC in Minooka," The Scranton Republican (Scranton, Pennsylvania), May 9, 1936. Photo courtesy of the FDR Presidential Library and Museum.