Above:

Above: This is one of several photographs that appeared in the March 27, 1939 edition of

LIFE magazine. It shows a scene from the WPA's New York production of

Pinocchio.

LIFE described the play as "one of Broadway's most charming productions."

Photo scanned from personal copy, and used here for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Above: This photo appeared in the March 23, 1939 edition of the Daily News newspaper (New York City), with the following caption: "Edwin Michaels expects to have to wear this makeup all Summer - for the WPA Federal Theatre has a hit on its hands in 'Pinocchio,' at the Ritz Theatre. This story of the legendary puppet, whose nose grew every time he told a lie, will be given its seventy-fifth performance tonight and there is a large advance sale at the box-office." Photographer unknown, courtesy of newspapers.com, used here for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Above: A WPA poster, promoting the WPA production of

Pinocchio. According to the

Internet Broadway Database, WPA's

Pinocchio started on Broadway on December 23, 1938 and ended on June 30, 1939, with a total of 197 performances. Author Susan Quinn writes: "The production turned out to be a hit with adults as well as children...

Pinocchio was playing to standing room only and contributing to the best matinee business Broadway had enjoyed since 1929" (

Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times, New York: Walker & Company, 2008, p. 265).

Image courtesy of George Mason University.

Above:

Above: As indicated by this WPA poster, the WPA performed

Pinocchio in various cities across the United States, with different cast members at each location (the Alcazar was a theatre in San Francisco, not to be confused with the currently-named "Alcazar Theatre").

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above:

Above: Hallie Flanagan, the director of the WPA Theatre program, included this photo in her book

Arena (Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940). It shows Edwin Michaels playing Pinocchio and Gabrielle Duval playing the marionette ballerina. Writing to the Dies Committee (the congressional committee that ultimately helped destroy the WPA's popular Federal Theatre Project), Flanagan said: "You might be especially interested in this production, not only because it represents one of our major efforts in the field of children's theatre, but because it is a visualization of what we have been able to do in rehabilitating professional theatre people and retraining them in new techniques. In

Pinocchio we use fifty vaudeville people who were at one time headliners in their professions and who, through no fault of their own, suddenly found themselves without a market" (p. 346).

Photographer unknown, used here for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Above:

Above: Two of the vaudeville performers that Hallie Flanagan referred to--

- Ettore Maggioni and Helen Goluback--were described in the official program for WPA's

Pinocchio. Vaudeville and "Variety" acts were dying out by the 1930s, and many of the performers are completely forgotten today; but they were great and talented performers in their heyday (late 1800s / early 1900s).

Image scanned from personal copy.

Above:

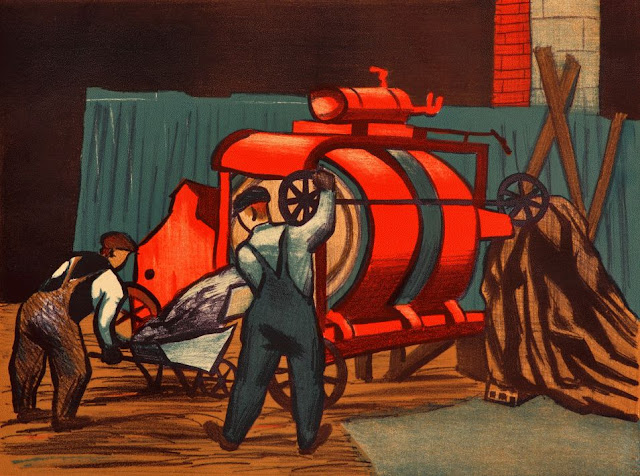

Above: A scene from WPA's

Pinocchio, exact date and location unknown. Set designs for the play were elaborate, and music was provided by the WPA's Federal Theatre Orchestra.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above:

Above: At the Ritz Theatre on Broadway, an audience enjoys a WPA performance of

Pinocchio, December, 1938. Despite Director Flanagan's letter to the Dies Committee, Congress shut down the WPA Theatre and made sure that children could never see

Pinocchio again (with one exception, 11 years later; more on that below). At the end of the final Broadway performance, Pinocchio was put in a coffin "which bore the legend: 'Born December 23, 1938; Killed by Act of Congress, June 30, 1939'" (

Arena, p. 365).

The photo above appeared in the Daily News

newspaper (New York City)

, December 30, 1938, photographer unknown, courtesy of newspapers.com, used here for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Above:

Above: A costume design for WPA's

Pinocchio.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above:

Above: Another costume design for WPA's

Pinocchio.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above:

Above: This WPA poster advertises the WPA production of

Pinocchio in Boston, "Beginning Tuesday April 11th." The following day,

The Boston Globe reported: "The Federal Theatre brought to life last night

Pinocchio, the little Italian puppet of fairy tale fame, and took the large audience at the Copley Theatre on a rollicksome adventurous tour of the land of marionettes, Boobyland, to a big circus, and lastly to the bottom of the sea and inside a whale's stomach. Three acts and nine scenes of a 'land of let's-pretend,' filled with song and dance, high comedy, and picturesque scenes were unfolded deftly and expertly by the Federal Theatre group" ("The Stage, Copley Theatre, 'Pinocchio,'"

The Boston Globe, April 12, 1939, p. 12).

Image courtesy of George Mason University.

Above:

Above: This is a page from the official program for WPA's

Pinocchio. One thing you will notice is that the role of "Young Father" was played by Vito Scotti (1918-1996). Scotti was born in San Francisco and after making his

Broadway debut in WPA's

Pinocchio went on to become a prolific character actor, appearing in an

astonishing number of television shows from the 1950s into the 1990s.

Image scanned from a personal copy.

Above:

Above: The cover of the official program for WPA's

Pinocchio. Interestingly, if you go to the

Wikipedia page for

Pinocchio, which is fairly thorough, there is no mention of WPA's

Pinocchio (as of October 25, 2020), not even in the list of stage productions. Yet, WPA's

Pinocchio was a Broadway hit and likely had some degree of influence on Walt Disney's famous

Pinocchio animated film (see, e.g., Beth Fortson, "

Original Costume Sketches for a Production of Pinocchio, 1939,"

The Unwritten Record, a blog of the National Archives, January 19, 2016; and "

'Pinocchio' very special to son of author,"

The Morning Call, April 30, 2010). This is an interesting example of how the WPA's great public works and legacy have been forgotten by modern Americans.

Image scanned from a personal copy.

Above:

Above: Edwin Michaels as Pinocchio, in a scene at the Ritz Theatre. It's interesting to consider that this man, forgotten in time, helped to restore the Broadway economy from the Great Depression.

Photo courtesy of the Broward County Library.

Above:

Above: Edwin Michaels, ca. 1926, age 17. Not a ton of information exists on Michaels, but we know he was born in Philadelphia around 1909, on Lehigh Avenue, and attended Visitation School (which is also on Lehigh Avenue, and today is named "Visitation B.V.M. Catholic School"). In the mid-to-late 1920s he began making a name for himself as an exceptional vaudeville dancer and acrobat. His sister, Gertrude Michaels, was also a dancer, and spent several years with the Ziegfried Follies. It appears that Edwin reached Broadway at least three times,

Queen High, 1926-1927;

Tobias and the Angel, 1937 (another WPA production); and

Pinocchio, 1938-1939. He performed for another year or two after

Pinocchio, but then retired from acting to pursue a career in private business. But he returned to play

Pinocchio once more in 1950 (see below). After that, there is no concrete information on his life or even the exact year of his death. Rest in peace Mr. Michaels, wherever you may rest.

Photo from "Another Native Sun Scores a Success," The Philadelphia Inquirer

, May 2, 1926, p. 67, unknown photographer, courtesy of newspapers.com, used here for educational, non-commercial purposes.

WPA Pinocchio Returns!

WPA's Pinocchio must have been really, really popular... because 11 years later, in 1950 (seven years after the WPA ended - and thus not officially a WPA production), it returned, with the original WPA director, Yasha Frank, and two of its original actors, Edwin Michaels and Sam Lewis (the latter of whom used to have a successful vaudeville act, "Lewis and Dody," decades earlier). Pinocchio's return was for one week at Pitt Stadium (University of Pittsburgh), and newspaper accounts from the time described it as an extravagant and alluring production; apparently, children had to be restrained from running on stage and joining in on the fun.

And Edwin Michaels had one last moment in the spotlight:

"Edwin Michaels has come out of 'retirement' to recreate the Pinocchio role that he portrayed in the Federal Theater production. And he is superb. His every move has meaning and the importance of this is particularly significant when you consider that most of his work depends upon pantomime ability... For an evening of sheer pleasure get out to the Pitt Stadium some night this week" ("Pinocchio Charms Stadium Small Fry: Adults as Well as Youngsters Cheer Outstanding Production," The Pittsburgh Press, August 8, 1950, p. 14, emphasis added).

Above:

Above: This ad appeared in the August 6, 1950 edition of the

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph newspaper.

Image courtesy of newspapers.com, used here for educational, non-commercial purposes.