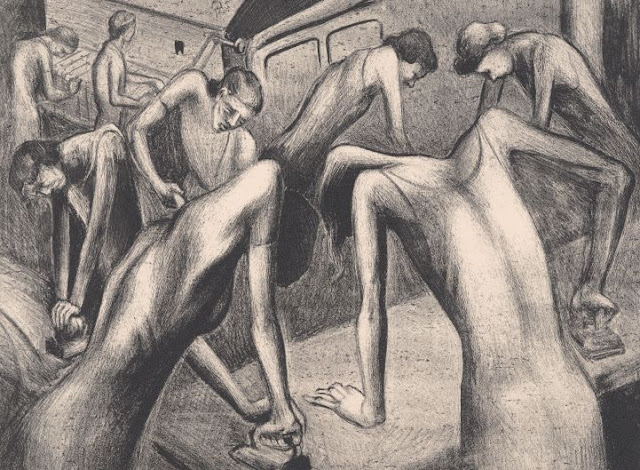

Above: Part of "Contemporary Woman and Justice," a painting in the Department of Justice Building, Washington, D.C., created by Emil Bisttram (1895-1976), while he was in the New Deal's Section of Fine Arts, 1937. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress and Carol M. Highsmith.

Above: The Portland (Maine) Municipal Golf Course, built by WPA, 1937. Between 1935 and 1943, WPA workers built 254 new golf courses and improved 378 others (Federal Works Agency, Final Report on the WPA Program, 1935-1943 (hereafter, FR-WPA), 1946, p. 131). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A game of Pick-Up-Sticks, part of a WPA recreation program in Seattle, Washington, ca. 1935-1943. Before television, video games, the Internet, and smart phones started isolating us from one another, kids and young adults would gather at recreation centers to converse, play games, shoot pool, dance, etc. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: The description for this photograph, ca. 1935-1943, reads: "A couple of skiers don their hickories in preparation to ascend Mt. Whitney Trail at Lake Placid [New York]. WPA constructed the Von Hovenberg Olympic Bob-run; repaired and maintained equipment and machinery... and constructed many ski trails." Across the nation, WPA workers created 310 miles of new ski trails and improved 59 other miles (FR-WPA, p. 131). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A WPA poster encouraging hiking. During the New Deal, workers in the Civilian Conservation Corps carved out 13,172 miles of new foot trails and maintained another 41,270 miles (Federal Security Agency, Final Report of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps, April, 1933 through June 30, 1942, p. 105). Americans still hike these trails today. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above: Sculpting in a WPA recreation program in Washington state, 1937. Art classes and art opportunities were plentiful during the New Deal. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: These young women are learning how to broadcast a radio program, part of a WPA recreation program in South Bend, Indiana, ca. 1935-1943. It's hard for us to understand today--with smart phones, Twitter, and streaming shows on the Internet--but radio was a BIG thing back in the day. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A Japanese girl rhythm band, in a WPA recreation program in Arroyo Grande, California, 1936. During the New Deal, children all across the nation had numerous opportunities for music instruction and music playing. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A WPA poster, promoting clean pools and swimming for health. Across America, WPA workers built or improved 2,073 pools (FR-WPA, p. 135). Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above: These young women are getting ready to enjoy their new WPA-built swimming pool in Jefferson County, Alabama, 1938. In Alabama, WPA workers built or improved 23 pools (FR-WPA, p. 135). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: Learning the basics of softball, part of a WPA project in Charleston, South Carolina, 1938. Across the country, the WPA helped set up softball games and softball leagues for women, men, and children. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A volleyball game, part of the WPA's adult recreation program in San Francisco, ca. 1935-1943. New Dealers felt that recreation wasn't just for kids, but adults too. In fact, President Franklin Roosevelt, in his Second Bill of Rights speech, promoted the idea that all American workers should have the "right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation." Today, of course, we've thrown that sentiment onto the ash heap of history. Today, we demand that all adults work ceaselessly for their millionaire & billionaire overlords, at 2 or 3 jobs if necessary, and for stagnant wages. "Recreation?? Bah hum bug!" Unfortunately, this "work-work-work, we-only-have-time-for-fast-food" lifestyle is probably a major reason why "Americans Just Keep Getting Fatter" (New York Times, March 23, 2018). FDR was right, we're wrong, and the proof is in our expanding waistlines. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: This WPA poster was recently made into a U.S. postage stamp. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above: These women are receiving instructions, as part of their work as youth leaders at a summer camp in Chepachet, Rhode Island, ca. 1935-1943. They are enrolled in the National Youth Administration (NYA). The New Deal's NYA offered jobs, training, and paychecks to millions of young men and women who were struggling financially. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: Two Camp Fire Girls take aim during a WPA recreation program at the French Creek Recreation Demonstration Project, Pennsylvania (today's "French Creek State Park"), ca. 1935-1943. The Camp Fire Girls organization has been around for more than one hundred years, and was founded on the principle that "girls deserved the outdoor learning experiences that boys had..." (today, it's co-ed and just called "Camp Fire"). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: Future aviators? A model airplane club, part of a WPA recreation project in Cincinnati, Ohio, ca. 1935-1943. For an interesting story about women pilots, see "Female WWII Pilots: The Original Fly Girls" (NPR, March 9, 2010). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A WPA poster advertising a Doll and Buggy Parade. Doll and Buggy Parades are still held today. For example, Kohler Village in Wisconsin is having their annual Doll Buggy Parade on August 2, 2018. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above: Some WPA recreation fun in Long Beach, California, ca. 1935-1943. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A WPA-supervised broomball game in Minneapolis, Minnesota, ca. 1935-1943. Did you know that there is an International Federation of Broomball Associations? Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A skier at the Timberline Lodge in Oregon, ca. 1938. In 1937, At the dedication of Timberline Lodge, President Roosevelt said: "This Timberline Lodge marks a venture that was made possible by W.P.A. emergency relief work, in order that we may test the workability of recreational facilities installed by the Government itself and operated under its complete control." Though it's had periodic challenges, the Timberline Lodge is "one of the few National Historic Landmarks that is still operated for the same purpose for which it was originally built" ("Eight Decades of Awe-Inspiring," Timberline Lodge). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.