Above: A WPA housekeeping aide bathes a child, while the mother recuperates in a hospital, Washington, D.C., 1938. Between 1935 and 1943, WPA housekeeping aides made 32 million visits to Americans who who needed help (due to illness or emergency) with housecleaning, cooking, and childcare (Final Report on the WPA Program, 1935-43 (hereafter, FR-WPA), 1946, p. 134). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: A WPA household trainee operates an electric clothes washer, Columbus, Ohio, ca. 1935-1943. Household trainees learned the latest techniques and technology for running the modern household (see, e.g., "Burlap Sacks, Orange Crates, Become Furniture in WPA Women's Project," (article also discusses WPA housekeeping aides), The Marion Star (Ohio), February 10, 1939). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: These WPA workers are doing the laundry at a hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, 1936. Laundry work isn't glamorous, and rarely well-paid, but who wants to be admitted to a hospital that uses dirty sheets, or stay at a hotel where the towels aren't cleaned from one visitor to the next? How valuable is clean laundry, and, do we pay that full value to the workers? Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

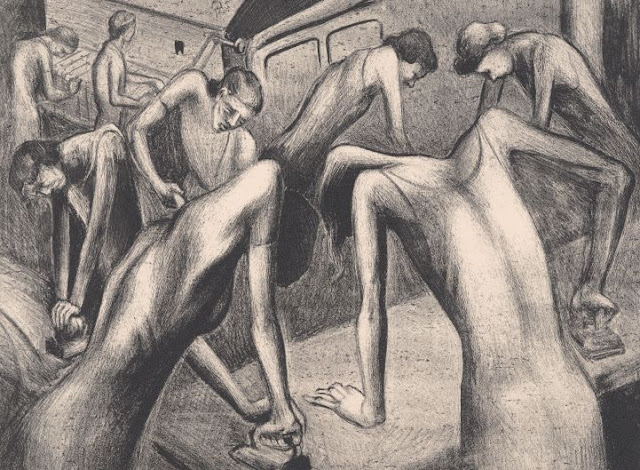

Above: "Laundry," an artwork by Joseph Leboit (1907-2002), created while he was in the WPA's Federal Art Project, ca. 1935-1939. The drooping heads and emaciated bodies of the women depict laundry work (or domestic work more generally) as gloomy and exhausting. The women in the foreground appear to be using their straightened, locked arms to keep themselves from collapsing. The woman all the way in the back seems to be either sleep-standing, or weeping, or praying for relief. Compare this image to the next. Photo courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Ackland Art Museum.

Above: A WPA poster promoting housekeeping jobs. This colorful poster, of a woman doing dishes with great happiness, stands in stark contrast to Leboit's "Laundry." Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above: Another WPA poster promoting housekeeping training and jobs. This poster has a classic 1930s look. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Above: WPA household training in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1936. The FR-WPA states, "Household workers' training projects offered instruction in a variety of household tasks, such as the preparation and serving of meals and seasonal house cleaning. Some of the projects included elementary training in child care and, where possible, trainees spent some time in local WPA nursery schools. Training on these projects usually lasted 12 weeks, and supervision was given by experienced home economists" (p. 90). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: "Scrub Woman," a sculpture by Gustave Hildebrand (1897-1950), created while he was in the WPA art program, ca. 1935-1943. A description for this artwork reads: "Gustave Hildebrand's sculpture Scrub Woman portrays an anonymous woman on her knees scouring a floor. Hildebrand brings attention to labor that often is 'invisible' to others." Image courtesy of the General Services Administration an Carol M. Highsmith.

Above: Another scene from the WPA household training in Pittsburgh, 1936. "In the period from July 1, 1935, through March 31, 1942, about 22,000 persons [across the nation] completed the WPA household workers' training course, and nearly 17,000 were placed in private jobs" (FR-WPA, p. 90). Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: Cleaning the bathroom, in a household training class in Columbus, Ohio, ca. 1935-1943. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Above: "Ladies of the Evening," an artwork by Don Freeman (1908-1978), created while he was in the New Deal's Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), 1934. The PWAP was a forerunner to the WPA's Federal Art Project. The women here are cleaning up after a show, and the woman in the balcony appears to be making fun of that upper crust of society that frequents the theatre - thereby marking the separation between (a) those who work, but don't make enough money to routinely enjoy the finer things in life, and (b) those who have enough wealth to luxuriate while others endlessly toil. This sort of class consciousness or class caricature appears in many of Freeman's works. Image courtesy of the General Services Administration and the Museum of the City of New York.

Above: WPA poster, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The importance of cleanliness and domestic work

Above: WPA poster, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The importance of cleanliness and domestic work

Housework, cleaning work, childcare, domestic work, homemaking, etc., are frequently unappreciated and/or underpaid. But they're very important. For example, the cleanliness and sanitation that we (usually) enjoy helps us to avoid many of the harmful bacteria, viruses, and parasites that plague third-world nations. Our lives would be much more difficult if we constantly had to deal with hookworms, hantavirus, lung-threatening molds, and flesh-eating bacteria.

Also, nannies and daycare workers watch over children, and contribute to their early development, so that parents can devote more time to advancing their careers, increasing their personal finances, and, in some cases, improving the nation. To a large degree, cleaning and domestic work--whether by a paid worker or a family member--provides the foundation for all other types of work.

So, let's have a greater appreciation for stay-at-home moms (and dads), nannies, house cleaning workers, sanitation workers, trash collectors, etc, and let's also remember the labor of those thousands of WPA workers who helped America get clean and stay clean.

Also, nannies and daycare workers watch over children, and contribute to their early development, so that parents can devote more time to advancing their careers, increasing their personal finances, and, in some cases, improving the nation. To a large degree, cleaning and domestic work--whether by a paid worker or a family member--provides the foundation for all other types of work.

So, let's have a greater appreciation for stay-at-home moms (and dads), nannies, house cleaning workers, sanitation workers, trash collectors, etc, and let's also remember the labor of those thousands of WPA workers who helped America get clean and stay clean.

No comments:

Post a Comment